You must have noticed the rise of monthly subscriptions in apps and online services, trying to force an uncancellable 12 months period onto the user.

TL;DR: This goes against the requirements to form a contract in civil law and therefore the contract is void.

Introduction

Most of Latin Europe is governed by civil law (France, Germany, Spain…), while the US and UK are governed by common law. They are distinct legal systems with roots dating back thousands of years (civil law comes from Roman law).

The two legal systems are quite alien to one another. For example, US readers might say something about how a contract needs “consideration“, a common law concept that doesn’t exist in civil law. Definitely not a requirement to make a contract there.

We’re going to dive into some civil law concepts and how they relate to subscriptions and in-app purchases. References to French law at times because that’s what we’ve studied and are more familiar with. Nonetheless this is expected to apply to most of Latin Europe with minor differences between countries if any.

Typical Monthly Subscription

An subscription may or may not be introduced as monthly, and may or may not actually be monthly.

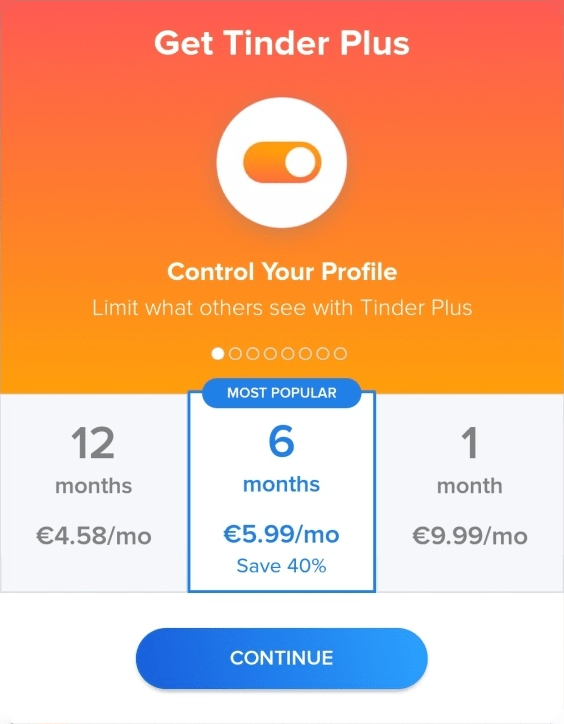

Here’s two samples from Adobe and Tinder, two well known product companies.

Contract Law

Mistake

Contract law has a fundamental concept that could be transcribed as “mistake” or “error” in English. See Erreur in French and Canadian law.

Warning: There is a related yet totally different concept called “mistake” in common law, not to be confused with! We will say error in the next paragraphs to avoid confusion.

In effect, the error is an incorrect understanding of an element of the contract, usually a fundamental element of the contract.

For example, one thinks they’re renting an office while the other thinks they are buying the office. Or one think they’re buying a car, while the salesman thinks they’re selling a different car [next to it in the shop].

One classic example given in French law school is a man buying land from a farmer, the man thinks he’s buying the land while the farmer thinks he’s selling the horses grazing on the land. (Note to urban readers: It is plausible, hectares of agricultural lands are cheaper than you think while horses are more expensive than you imagine).

Error will void a contract in full, retroactively as if it never existed.

To be recognized in court, the error must be genuine and plausible.

Dolus Malus

Contract law has a second fundamental concept of Dolus Malus (Latin), see French Dol or German Arglistige Täuschung.

In effect, Dolus Malus is to obtain the consent of another party [for a contract] through maneuvers or lies; or through omitting information that are known to be decisive for the other party. [Notice the two half here, each one sufficient on its own].

English languages do not have a legal term for dolus malus as far as we are aware. The concept itself is missing from English cultures and legal systems as far as we could search, while it is fundamental in civil law AND distinct from mistake.

A transcription could be “omission” or “deceit”, with a potential distant relation to misrepresentation or non-representation.

Interestingly, a Google translation from the German word above gives “willful deception”. Fair enough.

Omission/deceit can void a contract in full, retroactively as if it never existed.

Note: Scrolling through Google found only two related things, an old article on Roman antiquities on the university of Chicago and a thesis on Roman and Contemporary law from a university in Bulgaria. The term is notably absent from Wikipedia English entirely, except for one quote inaccurately assimilating it to fraud.

Void vs Void

Last but not least, there is a major difference between the meaning of “void” in common law and in civil law. They both recognize that a contract (or a clause) could be recognized as “void” and the similarly ends here.

In common law a “void” contract is akin to “voidable”. The contract can proceed as-is if both parties are okay with it. If one party is not okay with that, they must get the contract voided. A void contract is not void(ed), it will proceed by default.

In civil law a “void” contract is akin to “voided”. The contract is cancelled and considered to never have existed in the first place. It is much stronger and has a litany of implications.

For example if you buy a house and the contract is later recognized to be void (voided), it means the house never changed hands in the first place (it is not and was never yours). Officially the money never changed hands either.

You will ask what if it did? The answer is that it did not! It’s your money, if “they” “have” the money, the money is not theirs, it’s yours… albeit in not your bank account. (You get it, it’s strong and it’s gonna be a mess to deal with, more than can be covered in one paragraph.)

An English shorthand might be to say that it releases parties from all their obligations [retroactively]. (Although Lawyer Humor: It can’t release parties from their obligations, all obligations disappeared with the contract, there’s no obligations to be released from! Ahah)

As a company drafting contracts with customers to protect the company (and extract as much money as legally possible from customers while leaving as little recourse as legally possible) you really don’t want your contracts to be void. Special warning to English lawyers who might not take “void” that seriously because of the different definition.

For broader context, it’s extremely common for specific clauses to be voided (non compete or IP clause for classics), it’s rare for a contract to be voided whole. The things we are discussing here are precisely of the nature that can void a contract whole.

Subscriptions In Practice

In practice if you look at software subscriptions nowadays, it is often very difficult to understand what you’re signing up for?

- What’s the cost? What’s the term/schedule?

- What’s the total cost over a period of time really?

- Is it renewed automatically? When? How to stop renewal?

- How to cancel? Are there restrictions to cancel or fees?

- …

The very basis of the contract is the object (here what the seller provides and what the buyer pays). It’s problematic that it’s not well defined by the seller and that it can’t be understood by the buyer.

It’s no accident of course. The subscription is purposefully ill conceived in order to deceive (#dol).

Problematic is putting it lightly, the object is fundamental and an error or a dolus on the object voids the contract, most likely as a whole and retroactively.

Thus we’re getting to the crux of the article, most subscriptions are void because the customer was genuinely mistaken on what they were signing up for AND the subscription was deceptive.

Note the AND, either issue is sufficient to void the contract.

Of course subscriptions don’t have to be illegal, it’s perfectly possible to make a valid contract that’s paying monthly over a 12 months period. Subscription providers simply prefer to ignore contract law in order to generate more profit, hail to the automatically extending subscription that cannot be interrupted except on the last day of the year!

How to Make a Valid Contract?

A good start to make a valid contract would be to clearly state the payment terms and the total costs.

Yes the company should write in full text that the subscription will cost 120€ over 12 months, paid as 10€ every month.

Of course companies prefer to state “10€/month” in a big box on the payment page, not specifying the term or actual payment schedule. As long as they do so, they will continue to be misleading.

At a bare minimum, state 10€ a month -over 12 months- (in small letters under it). It does take a bit more room on the page and it’s fine (UX and marketing always hate to use more room yet the page has to satisfy legal requirements).

One alternative is to charge upfront, “5.99€ per month over 6 months” is clearly charged as 35.96€ once upfront. The upside is that it can avoid some confusion, it’s clearly all paid upfront and can’t be cancelled the next month. The downside is that if done wrong -purposefully or accidentally- it can be super confusing, why does it says X/month but is billing Y the next day.

Tinder does that unfortunately with an objectively misleading UI (thus a terrible example). The user taps 5.99€ a month but is billed 35.96€, visible the next day. Never agreed to that, that’s totally unexpected and shady. As far as I am concerned that is a perfect example of a contract that is void. The user would be 100% in their rights to ask for refund and charge back if not refunded.

Then there is the matter of cancellation and auto-renewals. A company is unarguably enticed to auto-renew everything and make cancellations as hard as impossible, for profits.

It’s further complicated on mobiles because of the limited space. These terms needs long full sentences of explanations, that don’t fit neatly in a single-screen pricing screen. The pricing ought to highlight the most important (really have to state the fixed period if there is one) and link to the full terms for reading, companies often fail to do that because reasons. Omission is one definition of dolus and is sufficient to make the whole contract void.

It’s possible to do a contract with a fixed period of engagement (12 months) and with some limitations to cancel. There is some case law to know and there is more coming up regularly. For example the user must to be able to cancel using the same method that was used to contract (if you could order by phone, you can cancel by phone). It’s complicated to draft so won’t get into that.

Abusive practices are either covered by recent case law specifically or in general by the mistake/dolus we have explained. In layman terms, if a person can’t figure out what they [inadvertently] subscribed to and can’t figure how to cancel an auto-renewal, there is certainly a problem with it, don’t have to look much further.

How To Get Your Money Back?

Unwanted subscriptions or auto-renewals happen and you want to get your money back.

First, look for a way to cancel and/or ask for refund in self-service. There should be one.

Second, contact the company to ask for refund explaining that it is a mistake and you want to cancel the purchase and get a refund.

Third, if not completed, contact the company again and insist. They legally have to refund [assuming the circumstances are met]. Leave them reasonable time to process the request (a few working days at minimum).

Fourth, if the company doesn’t reply or refuse to refund, refer to your payment provider to perform a charge back.

For transactions going through Google Play or App Store (themselves using a bank card), ask the store to revert the transaction, not the bank issuing the card.

Conclusion

These are basic principles of contract law that apply in Latin Europe.

We don’t think they are well known in the US (or even in Europe for that matter) but they should be. Legal, marketing and developers should all be aware of the law and consequences of their actions.

Looking at the typical software subscriptions and in-app purchases. It’s not a stretch to say that many many of them are unclear when not outright deceptive.

One last example in the purchase button for a dress in the game played by your 8 year old kid, that happens to charge real dollars from your bank account, maybe through an intermediate layer of virtual coins. That’s de-facto void for the reasons we’ve seen above and a few more (some jurisdictions have additional provisions regarding contracts and minors).

As a consumer contract law is on your side, these contracts are not valid, go ask for a refund and charge back when refunds are ignored. New cases being brought to court should consider all possible angles and aim to void the offending purchase contracts whole.

Corollary as a company, you have no excuse to be misleading, you should know it doesn’t satisfy requirements to form a valid contract. As a support employee or assimilated, you should not hesitate to refund if not else because you are legally required to.